CEOs frequently report feeling isolated and under-supported by their boards. All too often, a relationship with a particular director is the thread that holds things together along with the use of a trusted executive confidant, like Cliff Locks. And with fewer experienced CEOs serving on boards today, sitting CEOs are less likely to have a peer who truly understands what they are dealing with. How can boards strike the right balance between support and accountability so that they work more effectively with the CEO on long-term value creation?

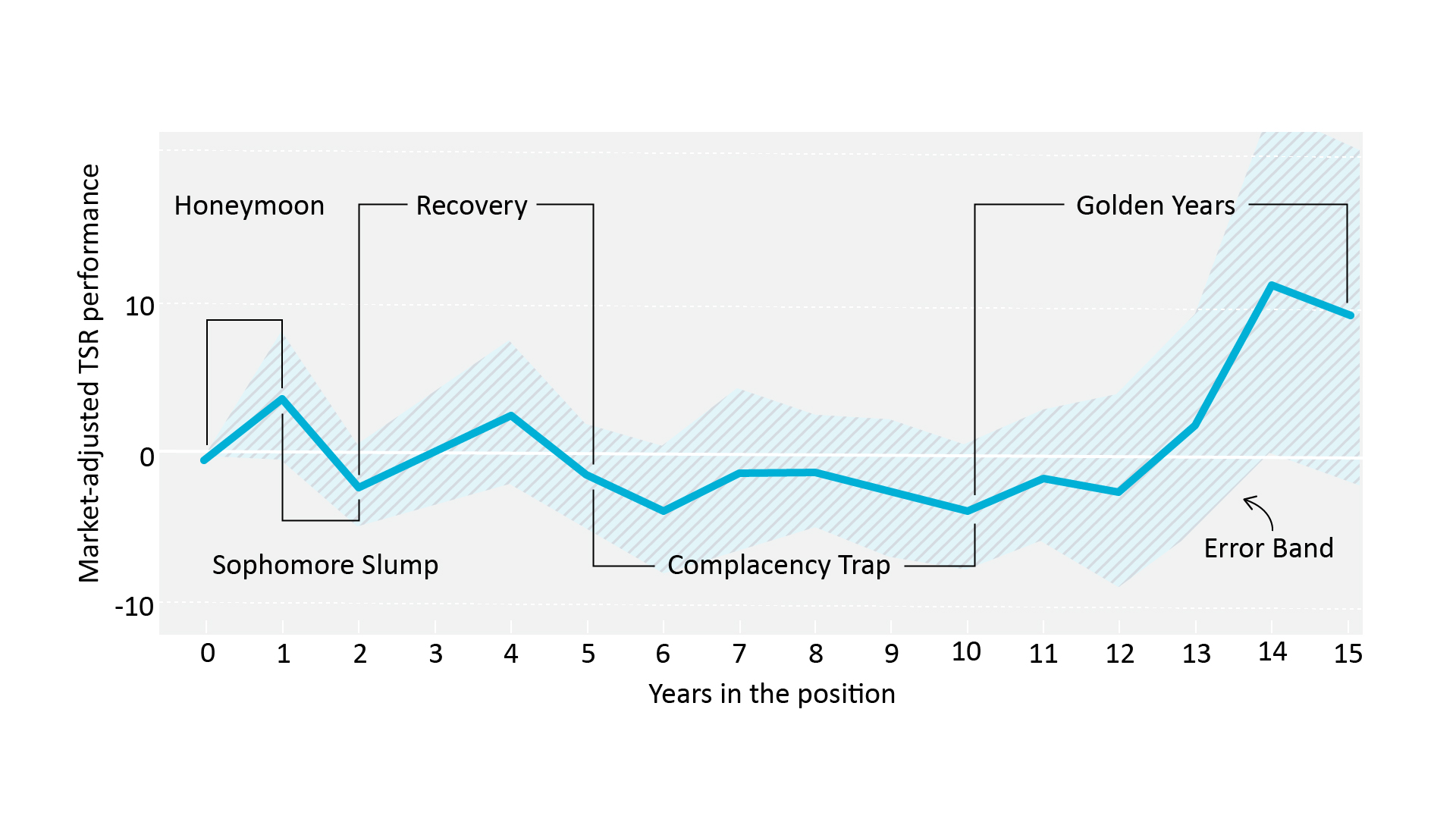

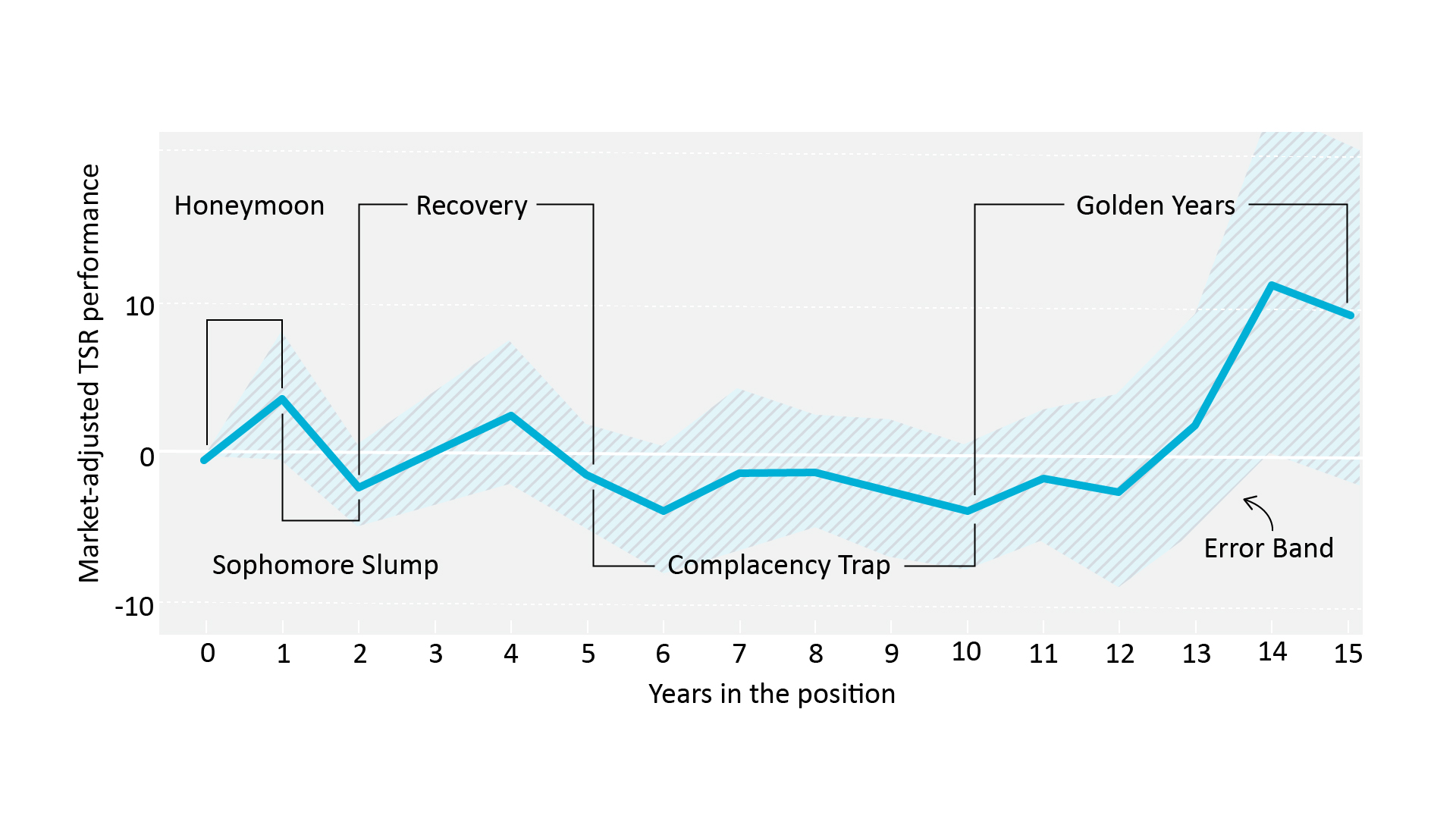

Spencer Stuart’s research into the CEO Life Cycle — a rigorous analysis of performance data for 750 S&P 500 CEOs, including more than 7,000 data points and interviews with more than 50 CEOs and board directors — shows that boards have a significant impact in shaping company and CEO performance when they encourage transparency and collaboration. Equally, CEOs need to establish and maintain trust by sharing information and engaging the board in meaningful dialogue, so that directors feel like they have sufficient opportunities to share their views and support the CEO. The CEO Life Cycle reveals the importance of the board’s support of the CEO at key moments, including investing time in the new CEO’s transition, creating alignment around realistic expectations throughout the CEO’s tenure, committing to the kind of reinvention and renewal required for future growth, and overseeing a robust, forward-looking succession process.

The CEO Life Cycle

Support the CEO’s transition

CEO selection marks the start — not the end — of a CEO transition. After a long succession process, boards tend to celebrate the wisdom of their decision and move on to the next thing, leaving the transition in the CEO’s hands.

Spencer Stuart’s research found that when boards and CEOs invested in building trust early, CEOs were less likely to experience a deep Sophomore Slump and were less likely to be ousted. Boards can help set the tone early by expressing their preferences on the ideal cadence and style of communication, the use of meeting time and their role in developing strategy.

“We want to be more engaged in building that strategy, and make sure that we are all owning that together.”

“We have told [the new CEO] that unlike the past, we do not want the CEO to bring to us a fully baked strategy. We want the CEO to bring us ideas. We want to be more engaged in building that strategy, and make sure that we are all owning it together,” one director told us. When the board views itself as a partner in developing strategy, it can help build trust with the CEO. “We’re all in this together. If we determine we’ve made the wrong decision, we’ve made it together. He’s not going to be out there on the limb by himself. That’s a change in tone from how we’ve operated in the past.”

It’s also important to begin building the personal relationships that will sustain the partnership over time. CEOs can feel unsupported when directors don’t seem to fully understand how difficult some big initiatives are to execute. Wise CEOs strive to develop one-to-one relationships with individual directors outside of the boardroom to seek advice and feedback on ideas, and this builds trust over time. Directors can encourage these interactions by hosting informal dinners and activities and making time to meet with the CEO one on one, even when it seems more efficient to plan small group gatherings. One CEO who commits to meeting with directors when traveling learned that meeting even with two directors at a time changes the dynamic significantly and is much less valuable for relationship-building.

Align on realistic expectations

Unrealistic and misaligned expectations are often at the root of adversarial board and CEO relationships. Every CEO journey is unique, but the CEO Life Cycle framework can help the board and CEO understand where they are and what may lie ahead, enabling them to discuss potential risks and opportunities at each stage. With less ambiguity, boards and CEOs can view performance in terms of the larger context and avoid overreacting in moments of doubt or tolerating mediocrity for too long.

Spencer Stuart’s research found that when CEOs and boards worked to stay aligned, they were more likely to create the conditions for driving long-term change and insulating the management team from unnecessary short-term pressure. During the Sophomore Slump period, for example, most CEOs experience a decline in performance. “In the second year reality often sets in. You’ve already taken advantage of the best opportunities and now have to refine plans and reassess your team,” explained one former CEO. How the CEO responds during this period and the support the board provides can set the stage for high performance or under performance in the succeeding years. “Either you survive,” the director said, or the board determines that “The CEO’s not working.”

Boards have an ongoing responsibility to monitor performance and recognize when it’s time to support, challenge or change the CEO. Amid a major strategic initiative with a longer-term payoff for the business, CEOs are looking for support. “It’s during those really difficult time periods, that’s when good companies have a solid and supportive board for the CEO.” But boards also need to be alert to changes in the CEO’s motivation or energy that could signal a need for a change. “When an individual has been in a role for five, six, seven years, they either get a little tired or they are ambitious and want to do more,” observed one director.

Boards can make sure they use their time with the CEO to check on progress and maintain alignment. A natural time for these conversations is the formal executive session. Reserving that time for a substantive, but intimate discussion of the issues that are on the CEO’s mind can help build a trusting environment and reinforce their mutual responsibilities. “It’s very important that the board handle that in an appropriate way. The board has to be open and appropriately supportive, surrounding the CEO with the resources needed to do what they need to do be successful.”

Boards can make sure they use their time with the CEO to check on progress and maintain alignment. A natural time for these conversations is the formal executive session.

Commit to ongoing renewal and change

A protective mindset can emerge when the strategy is working great and the team is humming. “There’s a tendency to think if the results are all right, the CEO’s doing a good job. Boards must be far more thoughtful about what’s around the corner and whether the CEO can meet those challenges,” one director told us. It is in the late stages of a tailwind period — rather than during headwind periods — when CEOs have freedom to adjust or place new bets on the future. As one board member explained, “By the time you smell the fire in the boardroom, it is often too late.”

Spencer Stuart’s research found that CEOs who are successful over the long term learn to reinvent themselves and their companies at a pace that is as fast as the world is changing, and boards of these companies expect and support reinvention. These leaders were more likely to reinvent their approach to leadership, transform the organization and think in terms of long-term impact or purpose, resisting complacency and incremental thinking.

It’s not just the CEO who has to guard against complacency and seek renewal. Boards also can get comfortable with solid performance and incremental change and stop pressing for the kind of reinvention and bold moves companies need to thrive today. “The world is moving in a certain place, and that’s what we have to compete against — not just our peers.” Boards will be in a better position to ask the right questions for the future when they have the right mix of expertise in the boardroom. “You actually have those discussions in the boardroom. The whole water level starts to go up a little bit.”

Directors also can fight complacency by finding opportunities for ongoing learning. These could include factory visits, meetings with customers or experts, or spending a day with management, which can help directors stay close to the business and understand the pace and intensity of the challenges facing the company, beyond what directors would hear in a boardroom discussion.

It’s not just the CEO who has to guard against complacency and seek renewal. Boards also can get comfortable with solid performance and incremental change and stop pressing for the kind of reinvention and bold moves companies need to thrive today.

Plan for CEO succession

CEO succession planning “is one of the biggest stumbling blocks for many who would otherwise be perceived as great CEOs,” one CEO told us. Ultimately, a CEO won’t be considered great if “at the end of the day, they didn’t instill the confidence in that shareholder base that the person taking their place is going to be able to follow their performance.” A PwC study found a much higher risk that successors of long-serving, high-performing CEOs will significantly under perform and be forced out of office. Our research found that the risk of failure was significantly lower when boards were actively involved in succession planning and the successor’s development.

The risks for boards neglecting succession planning are great. Transitioning CEOs is one of the hardest things a board has to do, and it’s even harder for boards to confront when performance is middling — when there is no burning platform for change. “There’s nothing really forcing you to do it,” said one director, describing the conundrum for boards.

Some CEOs are more willing than others to examine their own performance and motivation. Said one, “I was losing a little bit of my energy. I always say you need to step down when you can’t put on the uniform the way you used to.” But it’s up to the board to ensure that it has regular conversations about long-term value creation and the CEO’s time horizon. Understanding the natural headwinds and tailwinds CEOs will face during their tenure, the board should lead frank conversations about whether or not the CEO has the energy and ability to renew the strategy and organization to unlock value or the company’s next phase.

In addition to these conversations with the CEO, the board should actively manage a succession planning process that’s based on a forward-looking strategy for the company, which will shape the criteria for the next CEO. The process also should include thorough and thoughtful assessments of internal candidates with the goal of helping them get ready for the role within a certain time frame. Directors should get to know members of senior leadership in formal and informal settings.

The lead independent director, in particular, has to be a close partner to the CEO, setting the right expectations and tone from the beginning, closing the loop on questions and board feedback, and checking in periodically. Cliff Locks is available to be your lead independent director.

Embedding renewal in board processes

As part of their annual self-assessment, boards typically consider questions about the relationship between the board and CEO: How effective is the relationship? Does the board strike the right balance between its monitoring role and its advising role? Where does the board add value in the relationship? Where does the board misstep or struggle in that relationship? Our research suggests that boards should go further, not only asking about how effective the relationship is, but also how they can best support the CEO given where he or she is in the CEO Life Cycle.

For many boards, the compensation committee or nominating/governance committee can take the lead in CEO development and ensuring the CEO has the necessary support. An increasing number of compensation committees are expanding their mandate to include leadership development — sometimes changing their name to “management development and compensation committee” to reflect the broader mandate. Those that do are likely to consider a range of people issues, including leadership development, succession planning, CEO tenure and where the CEO is in the Life Cycle. Ideally, these conversations would happen a couple times a year to ensure the board and CEO are partnering on development.

While all directors should build a one-to-one relationship with the CEO early in his or her tenure, certain board leaders are better placed to facilitate board/CEO communication. The lead independent director, in particular, has to be a close partner to the CEO, setting the right expectations and tone from the beginning, closing the loop on questions and board feedback, and checking in periodically. Ideally, this relationship is one of transparency and mutual understanding about what excites and worries the other about leading the organization forward. During our interviews, CEOs and directors often expressed how frameworks like the CEO Life Cycle can help initiate a dialogue and chart a new approach to working together.